Credit Suisse had been in trouble for years; Silicon Valley Bank was a textbook bank run; Signature Bank was facing a criminal probe. Why has the press been reporting events with no obvious systemic impact as a systemic crisis?

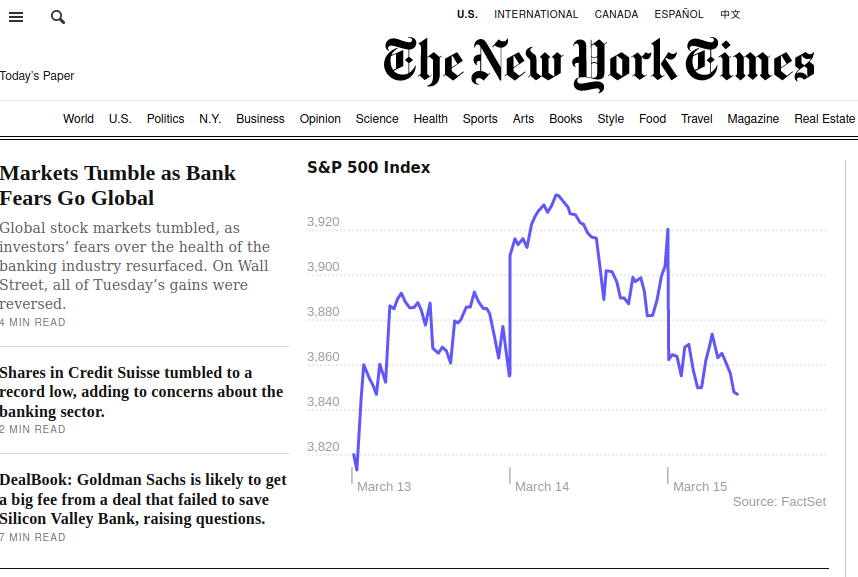

suggesting ordinary volatility of the S&P 500 is prima facie evidence of a market crash.

Background: The 2008 Financial Crisis, in a Nutshell

For those of us who were following the news religiously in September of 2008, you could be forgiven, at the time, for feeling a righteous sense of dread.

Back in 2008 the widespread adoption of an exotic and unregulated financial product known as the credit default swap—paired with a massive meltdown in the subprime mortgage market—almost destroyed the world economy. Credit default swaps—an experimental stock insurance product—resulted in companies like AIG and Lehman Brothers agreeing to take on massive liabilities in the event mortgage-backed securities, or companies potentially invested in these securities, went belly-up.

In September of 2008, one company—Lehman Brothers—was allowed to collapse after their exotic bets on toxic securities failed. After Lehman fell, other finance-related companies (e.g. AIG, Merrill Lynch) started looking like they were also on the verge of failure, and because major players in the financial sector were effectively tied together through credit default swap contracts there was suddenly a non-trivial risk that if one—or a dozen—major financial entities failed the entire global financial system could simply implode.

That didn’t happen because global financial regulators prevented it. AIG was not allowed to fail. Merrill Lynch was sold to Bank of America in a fire sale; Wachovia was sold to Wells Fargo; and so on. A total disaster was averted, though we all suffered a decade of economic malaise as a result of what is now a textbook financial crisis with its own historic title: the Global Financial Crisis.

The near-catastrophe of 2008 is what people think of when they talk today of “contagion:” a domino effect of one company’s failure cascading until lots of people find themselves broke or near-broke simply because their neighbors went broke. The bailout of AIG in 2008, like the bailout of Bank of America wasn’t done to simply prevent individual institutions from failing: it was done to prevent a cascading failure that could have made the Great Depression of the early 20th century look trivial by comparison.

That was in 2008 though. This is 2023. The issues facing the global financial system today do not appear to have parallels to 2008. And what is happening today doesn’t look like an obvious crisis.

The Players in the “Faux Crisis” of March 2023

Silicon Valley Bank

Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) failed due to a textbook bank run.

Bank runs occur when too many depositors try and withdraw their money at the same time, usually in a panic, causing a bank to fail because (as anyone who has seen “It’s a Wonderful Life” probably knows) banks make money by loaning out or investing depositor’s cash. Banks are usually only required by Federal regulation to keep a small percentage of their deposits, around 10%, in cash reserves. While bank runs are not good, they need to be understood in context because in the modern era these kind of runs are both extremely rare and relatively easy to prevent.

In hindsight, SVB was perfectly positioned for a bank run simply because it had a very large percentage (over 90%) of deposits not covered by government-backed deposit insurance, and depositor’s funds were mostly tied up in long-term—10 to 30 year—treasury bonds. While these bonds were effectively “risk free” if you held them until they matured, given the currently high interest rates for new Federal debt, selling these bonds immediately would result in a loss.

The lack of liquidity at SVB became a problem for the bank when something—seemingly a credit downgrade threat by Moody’s—caused SVB to sell a large number of treasuries at a loss so it could have more cash on hand. This decision appears to have spooked a select group of large account holders at SVB, and a panic snowballed into a textbook bank run.

SVB, unsurprisingly, didn’t have nearly enough cash to cover a surprise surge in deposit withdrawals, and it also reportedly struggled to borrow enough short term debt (and sell enough long-term assets) to remain solvent. Eventually either SVB or the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) realized the bank didn’t have the cash it needed to cover outflows, so the bank failed and the FDIC took over.

The FDIC is the reason bank runs are virtually unheard of in the modern era. Participating FDIC banks have all deposits up to $250,000 USD insured in full, but in recent history the FDIC has usually been able to recover and return all depositor’s funds, even those above $250k, in the event of a bank failure. In this case, because of public concern over SVB deposits above $250k, and out of fear of triggering a panic, the FDIC declared all deposits held by SVB to insured 100%, citing the relatively-easy-to-use “systemic risk exception”.

The SVB failure currently appears to have been caused by this bank doing nothing more dangerous or risky than having bought US Federal Government debt at interest rates that were—in hindsight—a bit too low and with maturities that were way too long. (Here is a Bloomberg News report on it, if you don’t believe me.)

The FDIC did not need to “bail out” the bank in the way people usually think of corporate bailouts, and the people who held stock or bonds issued by SVB lost every penny, as has been widely and repeatedly reported. It also appears depositor’s money was not actually lost, but was simply locked up in long-term government debt purchases or in loans issued by the bank. As a result, on March 15, the FDIC was able to quickly return $40 billion it temporarily borrowed from the US Treasury.

By offering assurances that depositors had full access to all their cash, the FDIC stopped an irrational flood of panicked withdrawals and allowed companies that banked primarily at SVB to make payroll. It also gave time to allow for a planned sale of either SVB or its assets to cover existing deposits.

There is nothing especially unreasonable or extraordinary about any of this. It’s not cause for panic; it is a cause for explanation and calm-headed news analysis. It’s genuinely interesting stuff, after all.

The failure of SVB did not appear to be due to exposure to exotic investments in crypto, tech stocks, or anything like credit default swaps: it appears SVB was a relatively boring bank with some unique liquidity problems not shared by many other banks, and it failed simply because too many people pulled out their money at the same time, and the bank didn’t have enough assets they could sell on short-notice to handle a bank run. Any bank, anywhere, can fail for this reason. That it happened here is not good, and that it may have been preventable is cause for investigation, but it’s also not a sign of contagion.

To sound like I’m quoting someone famous: a single bank failure does not a financial crisis make.

Signature Bank

The Signature Bank failure looks different from SVB in a key way.

Signature Bank was taken over by Federal regulators not because it failed in a bank run, but because its continued operation was viewed as posing a “systemic risk” to the US financial system. It later came out that Signature bank was facing a criminal probe over its anti-money-laundering practices.

It appears that by preemptively taking over the bank before news of a criminal investigation broke, the government may have gotten ahead of a speculative bank run similar to SVB. It was also seemingly a sign of strength, showing regulator’s willingness to act preemptively to prevent anything that even smells of contagion. Much like SVB, it did not appear that Signature lacked the ability to return money to depositors; it most likely though lacked the cash to handle a bank run, and fearing a bank run, regulators nipped the issue in the bud.

Good for regulators.

The story at Signature may still have a few twists and turns, but so far the regulatory system appears to be working as it should have. Yes, the system should have demanded that Signature and SVB be held to the same high standards as other banks were in the wake of 2008, and these banks should not have needed an FDIC takeover in the first place. But all-and-all this looks like an overwhelming success story in regulatory response, not a failure.

There appears to be no systemic crisis in the financial system—as regulators keep on saying, to the media’s deaf ears—and the primarily risk now seems like a few tech startups may lose access to their SVB and Signature Bank credit lines; credit lines that could—one would suppose—now be opened at other banks. This will be an inconvenience for these companies, sure, but it’s not a systemic crisis.

So SVB failed due to an old-school bank run. Signature Bank was closed seemingly to avert an SVB-style bank run. What about Credit Suisse?

Credit Suisse

Credit Suisse, a Swiss bank, appears to have been in trouble for some time, as anyone who reads the Financial Times daily probably could have told you. Problems with the bank, and speculation about problems with the bank, are old news.

People who use the Swiss banking system are also in a special category of banking customer, and Swiss regulators closely monitored the bank’s finances in the days before forcing it to merge with its rival UBS. Credit Suisse stood alone as the most troubled large bank in Europe, and it was forced to merge only after other financial institutions stopped lending it money to cover its huge investment losses.

The problems at Credit Suisse is categorically different than the problems at SVB, and the two do not appear to be part of a larger trend; Credit Suisse was simply a large troubled bank that has been a large troubled bank for some time. The bank’s failure is a fascinating story, and should be reported on in some detail, but one large bad bank is still just one large bad bank; it’s not all the banks, or even most of the banks.

“Crisis Actors“

The people trying to drum-up these small and localized events into some kind of overall “slow rolling crisis” or a “train wreck” narrative should not be taken seriously, as many may have taken financial positions which would result in them profiting in the event of a real crisis: their rhetoric should be viewed as cynically self-serving unless it’s shown to be otherwise.

While it’s a perfectly defensible position—sometimes even a public service—to short a stock of a company you know has problems, and then publicize wrongdoing that may ultimately drive the stock price down (e.g. Wirecard) it does not appear to be a defensible position to predict some vague upcoming financial crisis—not supported by any obvious evidence—to either pressure the Fed to lower interest rates to your benefit, or to undermine faith in an entire economic sector (e.g. mid-sized banks) you may have short positions on.

If you think individual stocks are overvalued you can say as much. It’s unacceptable though to peddle a narrative of a systemic collapse with the hope that you can profit off a panic after helping to cause one.

The Press

While the “crisis” narrative of the past few days does not appear to be primarily driven by short sellers and self-interested finance types, it does appear to be driven by newspaper editors or journalists who—on a slow news week—simply decided to report isolated events like they are part of a “system-in-crisis” narrative. (New York Times; Bloomberg News; Financial Times: I’m looking at you.)

If enough people start crying “contagion!” many people will start to believe it, and start to act like a wave of bank failures is imminent. There has been a large outflow from smaller banks in prior days that might not have occurred absent this “crisis” reporting. A small handful of banks may now be at elevated risk of bank failure for no other reason than this Chicken Little, “the sky is falling”-style rhetoric from the press.

And let’s be clear: no bank is positioned to withstand all their large (partially uninsured) depositors pulling out all their money all at the same time. Again, Federal regulations only require a small fraction of bank deposits to be kept in cash; the rest can be tied up in bank investments. Not being able to pay out all your deposits at a moment’s notice isn’t a sign of weakness in the banking system; it’s how banking works.

While I appreciate that the New York Times and other premium news publicans can only publish so many “ChatGPT and Blockchain are changing the world!”-style stories before readers move on to the next attention-grabber, there must be better ways to capture audience clicks than to make up a financial crisis when no data obviously points to a crisis. Yes, the stock market and banking stocks may have dropped today, or yesterday, or they may drop tomorrow, but how is that news? The markets have been gyrating wildly for no good reason for months, as have banking stocks.

It was apparent though throughout this last week that The New York Times (in particular) was anticipating a market collapse that never came, as they prominently featured a graphic on their front page to help readers watch—in real time—what they clearly hoped would be a “live” news-making market implosion. When they tried it on March 15th (see the image at the top of this post) the stock collapse they were hoping to cover didn’t happen. So they tried it again on March 17th and it also didn’t happen then. What’s wrong with the market?

Even the Financial Times fell into this trap, albeit to a lesser degree, and prominently showed on their front page the morning of March 16 how six banking stocks had dropped the prior day between 8% (Commerzbank) and 24% (Credit Suisse). While the coverage focused on Credit Suisse, the problem with making these stock movements news only becomes apparent when you realize that the lead for these events could easily read: “Credit Suisse stock price corrects as other banking stocks drop to lows not seen in four months“.

By the end of the weekend it turned out the real story wasn’t that Credit Suisse dropped 24% on Thursday but that it failed to drop more: the Friday before Credit Suisse was sold the bank had a stock market capitalization of $8 billion; it was sold on Sunday to UBS for $3.25 billion: the story is that Credit Suisse’s stock price should have dropped far more than it did before it was sold.

A Plea To Panic About the Right Things

So Dear Press: please take a deep breath; there is no reason to claim this is a financial crisis, and there are experienced and emotionally mature economists running the show, working diligently to ensure an irrational panic doesn’t become an actual crisis. One way this can become a real crisis is if everyone starts acting like this is a crisis and starts doing economically panicky things, like rapidly pulling their money out of smaller banks like First Republic for absolutely no good reason.

Yes, Credit Suisse failed, but—again—that was one large bank that has been in trouble for some time; it’s evidence of a failure in the Swiss banking system, for sure, but it’s not evidence of contagion.

If you want to get worried about a real crisis start paying attention to the soon-to-be-irreversible Global Warning crisis, the erosion of public health tools needed to control future pandemics, or maybe even how we have polluted the planet with a class of toxic chemicals that bioaccumulate and are almost impossible to filter from water with standard tech.

There are plenty of legitimate things to worry about where that worry can translate into meaningful action, not despair or panic. What would happen if the press only focused on the threats that are real, instead of imagining threats during a slow news week?

Postscript

This commentary was drafted on March 15-16, 2023, with minor additions and edits made on March 21-23, including this postscript.

As I publish this article on my blog there is no obvious evidence of a financial crisis. When I privately reached out to some journalist in the last week who claimed a “financial crisis,” asking about their sources, the ones who responded could not cite actual evidence of a crisis.

Despite the evidence, members of the press who do not believe that the events of the last two weeks constitute a “crisis” are solidly in the minority, and their observations of fact sometimes appear to be ignored or minimized by their own publications, including The Guardian Weekly (which on March 22 sent me an email newsletter with the title “As banks fail, is it time to panic like it’s 2008?”; including links to news articles in The Guardian talking about the “ominous” events of the last few days, and omitting a link to Jonathan Barrett’s mostly thoughtful March 20 article that raised doubts about whether this could even be called a crisis.)

While I personally dislike that we sometimes teach young students that “feelings are not facts” in this case the sentiment is so spot-on I struggle to come up with an effective counter-argument to it. After all, just because you are worried about a potential financial crisis does not mean there is an actual financial crisis or even a meaningful risk of one.

Multiple publications whose journalists and editors I ordinarily have enormous respect for have reported the facts of the last two weeks as if the facts themselves can’t believed: feelings of panic are the story, and dominate coverage of the story.

One reporter I emailed whose work has appeared in two of my favorite news publications, and who recently wrote a new commentary claiming the events of the last two weeks constituted a “financial crisis”, replied to me in a private e-mail saying that they didn’t think the head of the US Treasury Department, Janet Yellen, could be believed when she said “our banking system remains sounds” and openly questioned whether the press had any role in trying to trying to prevent a public panic.

While I understand the memory of the Norfolk Southern toxic train derailment in Ohio is still fresh on everyone’s mind—and there is a case where it did appear that public officials may have been deliberately ignoring evidence of harm in order to prevent a justifiable public panic—just because public officials tell you something is not a crisis does not automatically mean the opposite it true.

And while public health officials do have a track-record of misleading the public in the wake of dangerous chemical releases, the US Treasury does not have the same reputation when it comes to financial or economic crises.

To add to the evidence there is no sign of actual harm from two mid-size bank failures and one large Swiss bank merger, on March 22, in an obvious vote of confidence for both the health of financial markets and the economy, the United States Federal Reserve raised interest rates by a quarter of a percentage point. Not to state the obvious, but do you know what the United States Federal Reserve doesn’t do at the onset of an economic “crisis”? They don’t raise interest rates.

How did the New York Times then report this sign that the United State’s economy and banking sector were both in solid health? They did it with a surprising flair for sensationalism:

“Crisis! Panic!” And yet by the end of the day stocks were… up?

One of these stories, penned by Joe Rennison, amazingly claimed to have evidence that banks have pulled back on lending over the prior two weeks. How exactly do you get reliable data showing that all 1000+ American banks, in aggregate, pulled back on new lending in the last 14 days? I’ll tell you how: you don’t. You can, however, claim that banks have pulled back on new lending if you confuse speculative concern about a pullback in lending with factual evidence of an actual pullback.

This kind of “crisis” reporting, of course, has numerous drawbacks, including requiring you to ignore people on the ground who do not see evidence of a market crisis. But when you are trying to advance a narrative that is weakly supported by available evidence sometimes facts just get in the way.

Again, I’m loath to say it, but feelings are not facts. What is currently happening in the banking sector is a fascinating story, for sure, but it would be far more interesting if it was covered dispassionately.